Do We Really Have to Choose Between Reducing Pollution and Destroying Human Prosperity?

Category: Blog Articles By: Michael Durante

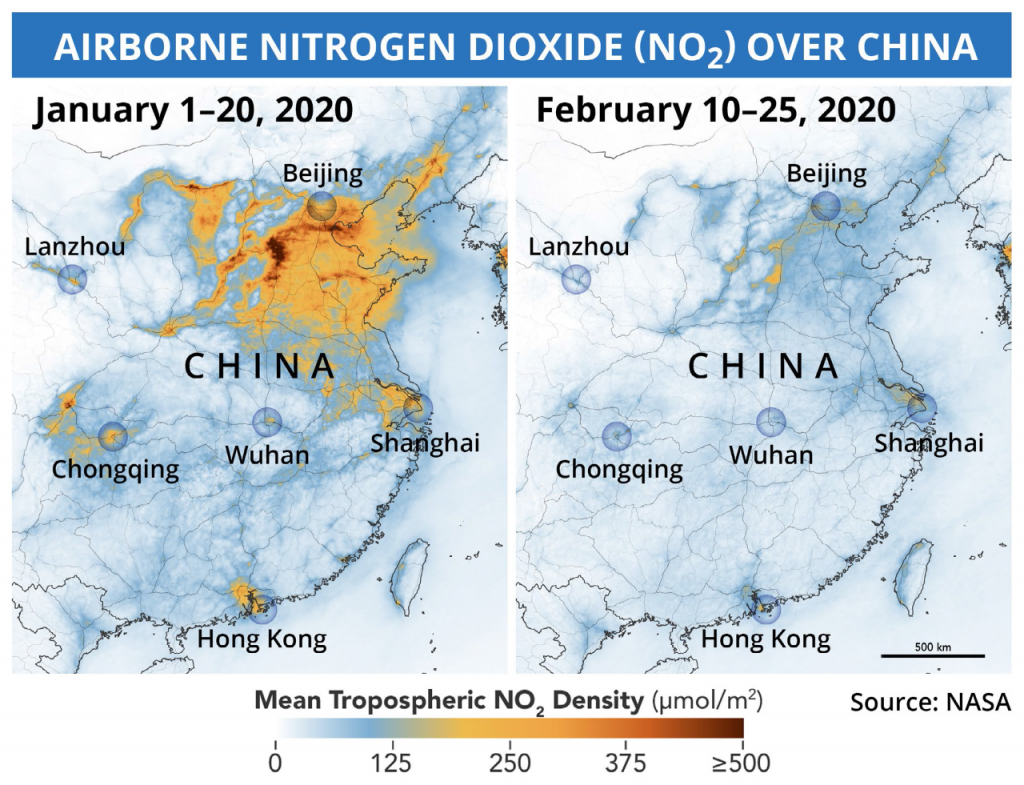

Scientists have noted that worldwide quarantines have dramatically reduced ground-level air pollution. In Paris, nitrogen dioxide readings have dropped a stunning 60 percent in the past few weeks. But what we’ve also learned in this pandemic is that austerity and abstinence, the long-offered solution to urban smog, will have a devastating impact on the human condition.

Unemployment claims in the United States are setting records, with nearly 10 million job losses in just the first weeks of reduced activity. It’s now obvious: the cure is greatly out-damaging the disease – at least in the short-term.

Therapeutic and preventive medicine is how we’ve managed life-threatening diseases historically. Today’s directives for the cessation of most business activity ad infinitum, is resulting in extreme human hardship. Yet we persist in presuming that draconian business restrictions are the solution for managing pollution.

Taxing human activity – the commonly proposed panacea for managing pollution – has failed miserably when tried. Carbon tax schemes, in this sense, were a dress rehearsal for what would happen to our economy should a pandemic occur. Now that we are all witnessing first hand the human sacrifice required by a near-total cessation of commerce, do we really believe inflicting that penalty on our business community is the best approach to reducing pollution?

Some would argue renewable energies are the answer to pollution reduction. But if that’s the case, why do renewable solutions remain almost 100 percent reliant upon tax credits, government subsidies, and utility conversion mandates?

In Australia, a 2011 carbon tax coupled with mandatory energy grid conversion resulted in a tripling of utility bills for Australians. If that wasn’t hardship enough, the country’s “sacrifice” only managed to achieve 6 percent renewable energy. In 2014, the Australians repealed the tax via an electoral overhaul of their government – in a landslide.

Which brings us back to the sacrifices we are all undertaking to suppress today’s pandemic. Outright cures are very rare in human history. For the most part, we manage disease with prevention and symptom management – and then we adjust and carry-on. This will likely prove true for COVID-19, and it is a lesson that is equally applicable to the pollution challenges we are facing.

Single vehicle emissions have declined over 70 percent since the 1970s. We didn’t “cure” for the unintended consequences of fuel combustion; instead, we managed the impact. The breakthrough was the invention of the catalytic converter, an early form of carbon capture technology. To date, it has been the only scalable success story in vehicle emissions-related pollution mitigation. All other strategies have failed, including public transit, high occupancy vehicle lanes and electric vehicles. Ironically, the latter produces as much as 50 percent more pollution than traditional vehicles due to their energy-squandering production process and high pollution energy sourcing.

Still, the rampant urbanization of our life style choices has superseded the catalytic converter. While cars run significantly cleaner than in decades past, we are adding more vehicles so quickly to the grid that we’re unable to bend the curve for air quality. New, complementary technologies are needed.

On-road emissions represent as much as 80 percent of urban smog, principally nitrogen oxides (NOx). The EPA measures NOx at 298 times the toxicity of carbon dioxide (CO2). That’s why PTI has been aggressively testing new road-level solutions as a therapy for mobile-sourced emissions.

Our results are no longer theoretical. We’ve achieved field testing efficacy as high as 60 percent in reducing NOx. Our solutions combine two previously proven technologies: the photocatalytic oxidation of pollutants, using naturally abundant photo-reactive materials combined with field-proven pavement preservation agents, which deliver those materials sustainably into the roadway substructure. We call them “smog-eating roads,” and these therapeutic compounds cost only a fraction of normal road maintenance.

As with other human health conundrums, success is ultimately found in reducing, rather than eliminating, negative impact – a scenario we expect to see played out in the wake of today’s pandemic before long. For now, stay well, and learn more about Smog Eating Roads.